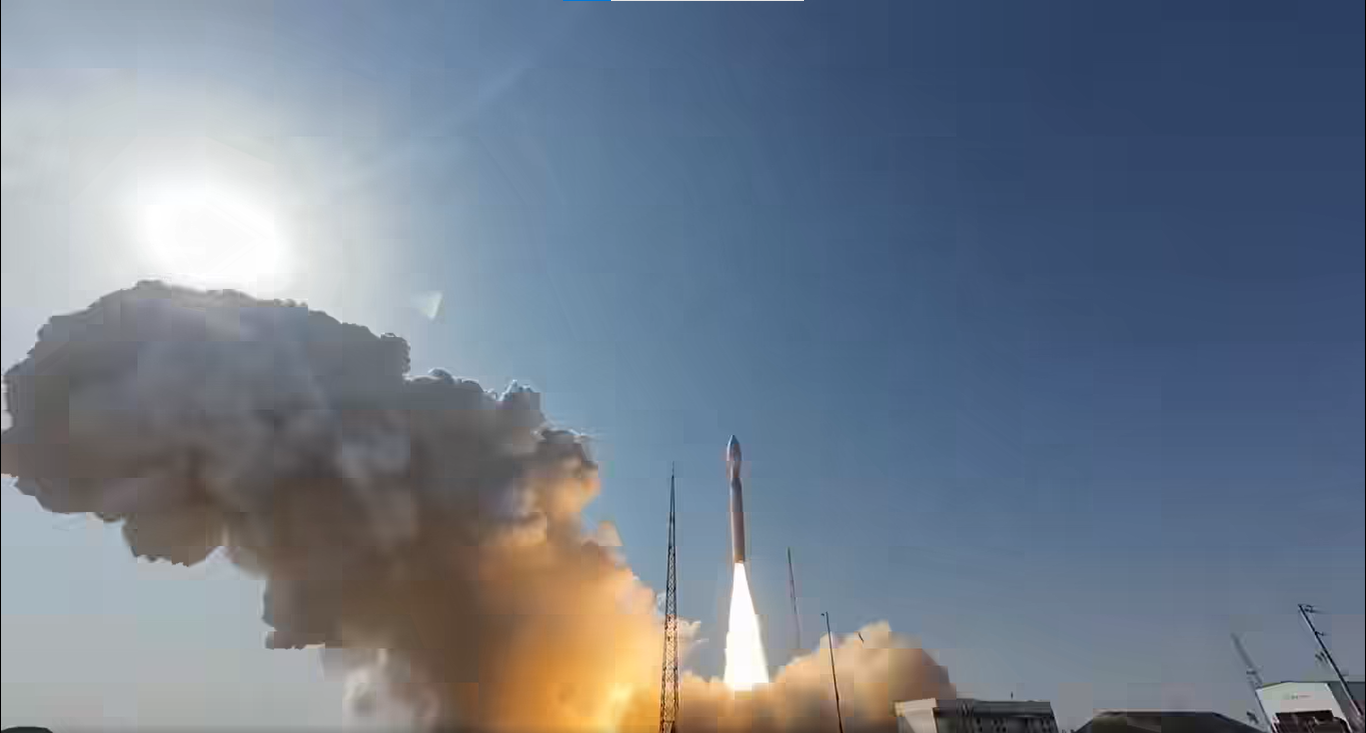

ISLAMABAD: In a strategic move to bolster its self-reliance in space and defense technologies, India on Sunday launched a communications satellite from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in Sriharikota.

The CMS-03 communications satellite, also known as GSAT-7R, was launched aboard India's indigenous Launch Vehicle Mark-3 rocket.

According to the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), the satellite will operate in geostationary orbit, providing secure, multi-band communications for the Indian Navy. Indian media described it as a military communications satellite designed to strengthen the Navy’s command, control, and surveillance network across the Indian Ocean.

The CMS-03 replaces the ageing GSAT-7 and marks a major upgrade in India’s military communications capability. ISRO said the launch also tested, for the first time in orbit, an indigenously developed cryogenic upper-stage engine, improving payload precision and fuel efficiency.

Expansion of India’s orbital ambitions

The launch continues a series of recent Indian space milestones. In January, ISRO’s GSLV-F15 successfully placed the NVS-02 navigation satellite into orbit, while in July, the joint NASA-ISRO radar mission, NISAR, was launched — a $1.5 billion project aimed at global environmental monitoring.

In September, ISRO transferred its Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV) technology to Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) to enable commercial production by 2027. The agency has also declared 2025 as “Gaganyaan Year,” with an uncrewed human spaceflight test featuring the humanoid robot Vyommitra scheduled for December.

Together, these steps reflect India’s push toward self-reliance in strategic space technology and defense applications.

Strategic recalibration post-May 2025 air engagements

India’s latest satellite focus highlights its efforts to restore strategic confidence following its setback in the May 2025 air engagements with Pakistan. During those encounters, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) had demonstrated superior coordination and situational awareness against advanced Indian aircraft, downing at least six Indian aircraft, including the top-of-the-shelf Rafale.

PAF Air Vice Marshal Aurangzeb Ahmed, in a post-engagement briefing earlier this year, credited Pakistan’s performance to its multi-domain operational capability and to the integration of real-time intelligence, cyber defense, and space-based data into air operations.

That experience underscored a key shift in modern warfare: information dominance — not firepower alone — now determines superiority. India’s new satellite is therefore widely seen as an attempt to close that gap and strengthen its command-and-control resilience through space-enabled systems.

Pakistan’s growing space cooperation

Pakistan has also accelerated its own space program through its space agency, the Space & Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO), in partnership with China. In January this year, SUPARCO launched the Electro-Optical Satellite (EO-1) to support agriculture, resource mapping, and disaster management. In October, it launched its first hyperspectral imaging satellite (HS-1) aboard a Chinese rocket, enhancing capabilities in environmental monitoring and precision agriculture.

Pakistan has also joined China’s astronaut training program, with two candidates preparing for a future mission aboard the Tiangong space station in 2026. Additionally, the PAKSAT-MM1 communications satellite completed its first operational year, expanding national connectivity, e-learning, and telemedicine networks.

Budgetary gap and road to autonomy

Official documents reveal a stark contrast in space program funding between the two countries. Pakistan’s SUPARCO operates on an annual budget of roughly $120 million, while India’s ISRO receives around $1.6 billion — a nearly 14-fold difference that highlights the scale of Pakistan’s resource constraints.

This financial disparity largely explains Pakistan’s reliance on external partnerships, particularly with China, to advance its space capabilities. While such collaborations provide access to cutting-edge technology and help bridge immediate gaps, they also highlight the challenges Pakistan faces in achieving long-term self-reliance and fostering indigenous innovation in its space sector.

Under the National Space Policy 2024 and Space Vision 2047, Pakistan aims to build self-reliant capacity by developing domestic satellites, indigenous launch vehicles, and a sovereign data network. Experts say achieving that goal will require greater investment, local manufacturing, and a skilled technical workforce.

Space: the new strategic frontier

The growing focus on orbital infrastructure reflects the changing nature of South Asia’s defense landscape. As India expands its military communications network through space, Pakistan is deepening cooperative development to ensure access and capability.

Both countries now view the space domain not merely as a scientific frontier but as a core element of national security, a shift that places information dominance and satellite communications at the center of regional deterrence and defense planning.