ISLAMABAD: Afghanistan’s interim Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi is on an official seven-day visit to India, emphasizing the potential of Iran’s Chabahar Port as a vital trade link between India and Afghanistan.

The visit, delayed earlier due to visa clearance issues, marks the first official trip by an Afghan interim minister to India since the Taliban takeover. Previously, India’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval visited Kabul in January 2021 during former president Ashraf Ghani’s tenure.

Addressing a press conference at the Afghanistan Embassy in New Delhi, Muttaqi underlined the significance of Chabahar Port, calling it a “good option for trade.” He urged both India and Afghanistan to “remove obstacles” to its full utilization, noting that “US sanctions have complicated operations.”

Chabahar is not a new trade idea for Afghanistan. Successive governments have explored it as an alternative route connecting Afghanistan to global markets through Iran, bypassing Pakistan. Yet, questions remain over whether it can become a reliable trade corridor that benefits Afghan traders and strengthens regional ties.

Why Chabahar matters for India?

Located along Iran’s southeastern coast on the Gulf of Oman, Chabahar holds strategic importance for India. It lies just 550 nautical miles from Gujarat’s Kandla port and offers New Delhi a direct trade corridor to Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Europe, circumventing Pakistan.

Since 2016, India has invested heavily in the project, spending nearly half of its allocated 4 billion Indian rupees. A year ago, India signed a 10-year agreement with Iran’s Ports and Maritime Organization to manage and develop the port through India Ports Global Limited (IPGL).

The initiative is part of India’s broader vision to integrate Chabahar into the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), linking India to Russia via Iran. Originally proposed in 2003 as a counterbalance to Pakistan’s Gwadar Port, developed under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the Chabahar project has faced repeated delays due to sanctions and bureaucratic hurdles.

Challenges facing the project

Despite India’s commitment, challenges persist. Afghan experts say Kabul remains skeptical of India’s reliability as a partner.

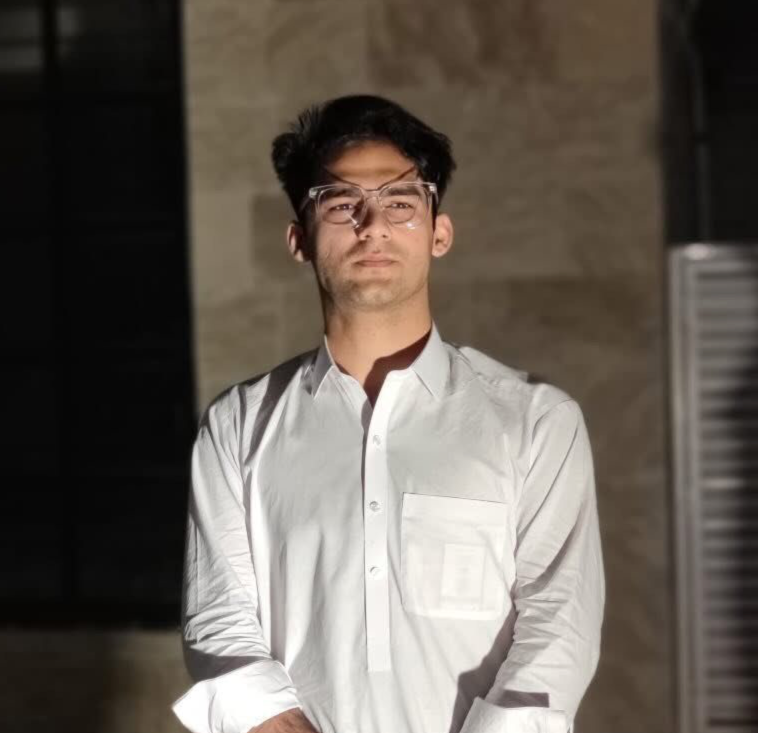

“Afghanistan continues not to see India as a dependable ally because New Delhi has traditionally remained distant from Kabul,” said Zia Ur Rehman, a Pakistan-based expert on Afghan affairs, speaking to Pakistan TV Digital.

He added, “India’s renewed interest in Afghanistan is driven by geopolitical signaling aimed at maintaining influence along Pakistan’s western border.”

India’s caution stems from its fraught history with the Taliban. The hijacking of an Indian Airlines plane to Kandahar in 1999 and the 2008 Kabul embassy bombing, both linked by India to Taliban elements, continue to shape New Delhi’s approach.

Meanwhile, Afghan traders remain reluctant to abandon the shorter and cheaper trade routes through Pakistan. “Chabahar increases transport costs, and those dealing in perishable goods cannot afford delays of several days,” said Qudrat Ullah, a local trader speaking to Pakistan TV Digital.

Sanctions and strategic setbacks

Complicating matters further, the Trump administration’s decision to revoke the US sanctions waiver on Chabahar has disrupted India’s plans. The exemption, granted in 2018, allowed India to operate freely at Iran’s Makran coast despite broader sanctions on Tehran.

“This move will disrupt New Delhi’s strategic and economic ambitions in Iran and Central Asia,” said Rehman, adding that the decision exposes Indian operators at Chabahar’s Shahid Beheshti terminal to punitive action under the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act (IFCA).

As Afghanistan’s acting foreign minister pushes for renewed cooperation, India faces a delicate balancing act, navigating strained regional dynamics, economic sanctions, and a skeptical Kabul, all while striving to keep its Chabahar ambitions afloat.

NOTE: $1 was equal to ₹88.72 (Indian Rupees) at the time of publishing of this article.